The paper is warm.

It is warm because it has just passed through iron. Pressed. Crafted by oiled hands. The letters moist. If I press my thumb firmly, it comes away blackened.

The cover blares: Common Sense.

The words sit without apology. No author. No preface. No softening phrase to make a reader feel clever. I notice, the paper’s cheapness. The faint roughness where a blade cut unevenly. Ink. Iron. Ideas.

Behind me the press moves. The sound rhythmic. The press pounds, paper passes. The machine does not care what it is printing. Men make machines, and machines make men.

Boys stack sheets. Mr. Bell, the printer, yelling. Thinking in numbers. Copies. Speed. Where they will go. Who will carry them.

I hold the pamphlet with both hands. I am aware, suddenly and sharply, that this is the last moment it will ever belong to me. Once it leaves, it will be read aloud in taverns. Folded into coats. Quoted badly. Misunderstood. Improved upon. Used. I have written many words. None like these.

Men believe they choose their words; then we learn words choose men.

For a moment, I realize this is reckless. Men want Truth, yes. Truth, only if it costs nothing. We want comfort. We want a crown. We want excuses.

The press moves again. Another stack forms.

I fold this pamphlet once, and slip it inside my coat. It rests against ribs, warm as if alive, and I understand with calm terror that whatever happens next has begun.

Outside, the air has teeth.

Philadelphia in January does not merely chill you. It insists. Cold creeps through cloth, through caution, through courage we counterfeit. The sky is the color of a leaden weight, pressing down.

I walk. My boots find slick patches where the city never quite dries. The streets are busy. Faces tight. Men look past one another. War makes cowards of eyes before it makes cowards of hands.

I turn into a narrower lane, away from the press and its thumping certainty, and the memory comes uninvited, as memories do, not as a story but as a physical fact: The room.

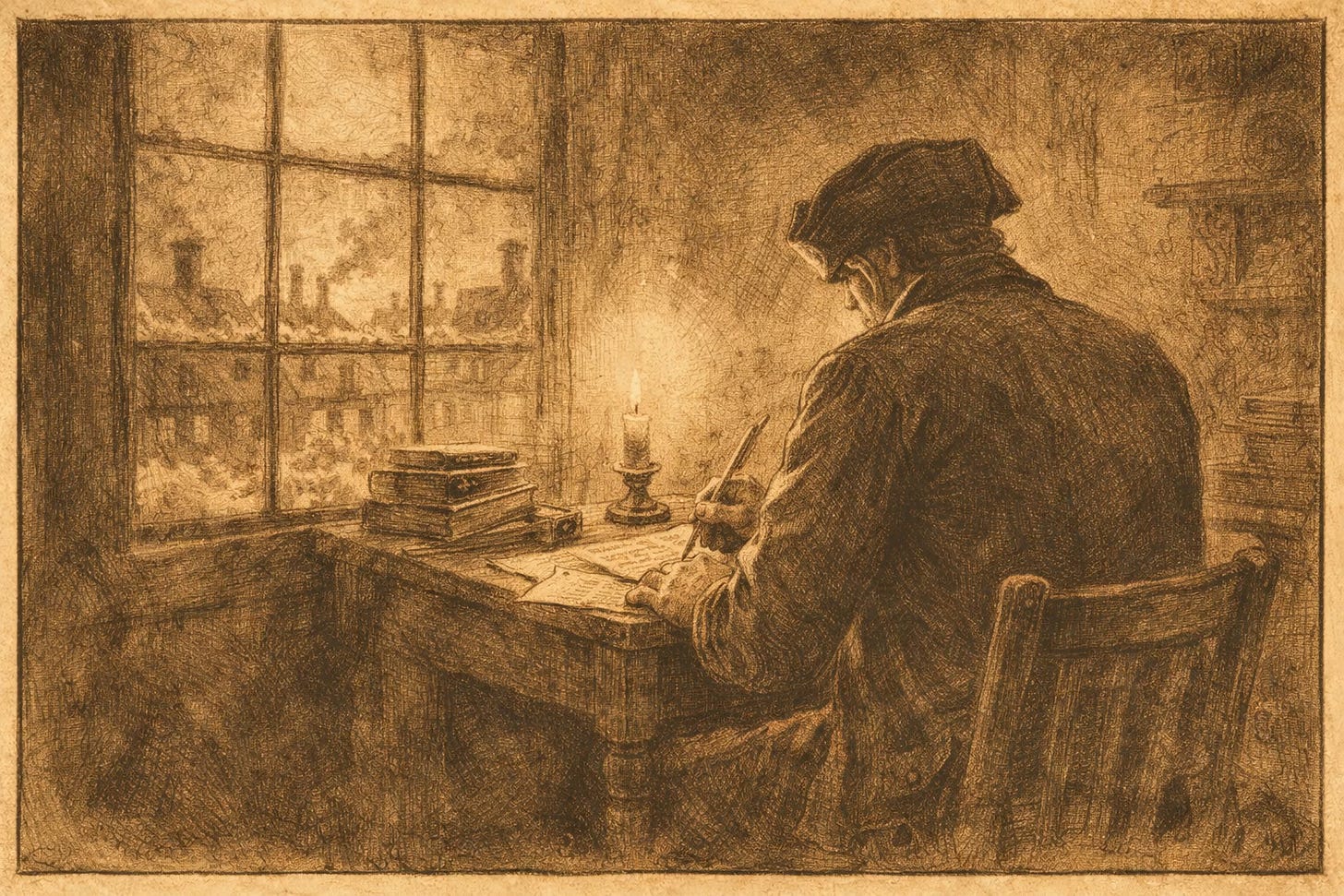

A rented space that smelled of damp wood and other people’s meals. A bed narrow enough requiring I learn to sleep on my side. A chair. A unstable table. The window badly sealed.

I wrote wearing my coat most nights. Not out of drama. Because the room was cold and the work did not wait. Ink thickens when chilled. So do hands. You learn quickly what survives cold. Clear sentences. Everything else freezes and breaks.

People like to imagine writing as comfort. A desk. A window. A kind of permission. They imagine the writer fed, rested, insulated from interruption. They imagine quiet as a gift. It is not like that. A city never stops. Wagons on stone. Voices rising and falling. Cups struck hard against wood. Somewhere, always, a hammer finding its mark. Even when it went briefly still, you could hear the noise lining up, ready to return. Silence in a city is not peace. It is only a breath held.

And then there is paper.

I did not have much of it. Paper costs money. So do mistakes. I could not afford sentences that admired themselves. I could not keep a paragraph that landed softly when it needed to strike. I wrote the way men travel when they do not know how long the road will be or what they will be allowed to carry. You take what works. You abandon what flatters. Weight matters.

Every day men spoke of reconciliation as if words could unspill blood from Lexington, Concord or Boston. I began to hate polite phrases. I began to hear them as chains. Power loves polite men.

When men want comfort, they call it reason; when men want power, they call it reason; when men want to hide, they call it reason.

There were moments, too, of something like fullfillment. A sentence landing cleanly. A thought that had been a knot in my head suddenly pulled straight. Those moments did not last. But they were enough to keep me writing when my hand hurt, when eyes blurred, when the candle guttered and the room filled with wisps.

Sometimes, late, I walked. Down at the waterfront where air carried tar and fish and the stale sweetness of spilled rum. Men there spoke plainly. They did not dress fear in philosophy. They knew hunger. They knew coercion . I listened.

When I went back, I tried to make my words fit their mouths. If a sentence could not be spoken by working men, I cut it. If an argument required a gentleman’s education, it was axed.

I did not “compose” Common Sense so much as carve it out of our discontent.

Back on the street, I feel the pamphlet. I pull my coat tighter.

I think of Mr. Franklin.

Not as a sage. Nor as a man who understood instruments: Kites. Presses. Words.

More as a mentor.

He knew which forces could be guided and which must be endured. When he spoke to me in London, he did not tell me what to think. He told me where to look.

“Write so that the common man may understand,” he said. Do not write for those who agree. Do not adorn argument. Decoration is an evasion.

It was not radical advice. It was practical. Franklin favored what worked.

I carried it with me. When I sat in my rented room, pen stiff, I did not imagine Plantation Lords reading. I imagined a man with cracked hands reading aloud to friends. I imagined the pauses. Where he might stumble. Where he might look up and say, Amen.

I stripped sentences naked. I chose words already living in people’s mouths for generations. Bible words. Market words. Plain words. I avoided cleverness the way one avoids thin ice.

Franklin understood what many men of learning don’t: That obscurity is not depth. That a complicated sentence hides a timid idea. Clarity is dangerous precisely because it leaves no room to pretend.

When I argued against monarchy, I did not do it as a philosopher. I did it as a man who had seen power up close and found it disappointingly human. I did it as a man who must pay taxes by forgoing needs.

Some men will trade conscience for comfort, then call the bargain civilization.

Kings, I wrote, are no more than mortals. Often worse, because they are spared the consequences that correct others. This was not theory. It was observation.

I did not cite Locke. I did not parade history like a trophy. I wrote as if the reader had already lived long enough to know when something was wrong and only needed permission to say it.

Now, walking through Philadelphia, I feel an echo of Franklin’s advice clearly. Words are sharp arrows. Once released, they do their work without you. If you have aimed well, they will travel farther than you can follow.

The danger, is not that people will misunderstand you. The danger is that they will.

I turn a corner and the wind cuts. Somewhere behind me, the press keeps moving. Somewhere ahead, men will read what I have written and feel something.

I walk on, unnamed, carrying the quiet knowledge that advice given in a London pub had just been converted by iron to ink on paper and risk.

Philadelphia is always chatting.

It talks in bursts and fragments, in half-finished thoughts exchanged at corners and counters. It talks through the hiss of frying fat, the creak of ropes at docks, the scrape of chairs on tavern floors.

We think we choose our beliefs; our beliefs choose our fears.

I slow my pace and let the yak wash over me.

Two men argue near a cart about the price of flour. A third interrupts to complain about the Committee, about rules multiplying faster than sense.

Power makes rules, and rules make power.

There is still too much careful language in the air. Too much hope that someone else will solve the problem if only approached correctly. Reconciliation is spoken of like a prize. Men speak of the king as if a distant uncle, misguided but well-meaning.

I hear England in their voices. Not an accent. Their habits.

A king is a habit; a habit a chain. We do not obey because we believe; we believe because we have obeyed.

In taverns, the talk grows louder and less precise. Someone pounds a table. Someone laughs. A man says he will not be ruled by Parliament. Another says he will not be ruled by a king. The difference between those statements is the distance between a protest and a revolution.

I learned quickly which arguments fall short. Which provoked silence rather than assent. Silence is more honest than applause. When men fall quiet, they are measuring the cost.

I wanted words that could survive being read aloud by men who had never thought themselves political. Sentences less like instruction and more like recognition. I borrowed the cadence of scripture not because I wished to invoke God, but because scripture had already trained people to listen. It taught them how to hear moral claims without footnotes.

As I walk, I catch my reflection in a darkened window. A man of no particular consequence. No uniform. No badge. A stranger to most I pass. That anonymity feels suddenly useful.

Near the river, the smell changes. They do not waste time on abstractions. They know what it means to be ordered about by someone who does not understand labor. When they speak of liberty, they speak of days and wages and the right to say no without punishment. I wrote for them.

I imagine them unfolding the pamphlet. Squinting at the title. Reading a line aloud. I imagine the moment when the argument shifts from grievances to being about legitimacy. That is where discomfort arises. That is when the ideas become dangerous.

The city listens even when it pretends not to. It absorbs phrases. It repeats them badly at first, then better. Words enter circulation the way coins do. Worn smooth. Detached from origin. Used for purposes a maker never intended.

I am aware now of how small my part is. I have delivered a script into the city’s mouth. What it does with it will not be polite. It will not be orderly.

This is as it should be.

I pull my collar higher and move on.

I remember it not as a flash of courage but as a tightening. A sense that the room had grown smaller. The air had thinned. I had been circling an idea for days, maybe weeks, letting it show itself indirectly, the way men do when they hope Truth will volunteer itself.

Blame Parliament. Blame ministers. Blame corruption. All of this was safe. All familiar. It allowed men to remain loyal to the structure while condemning its occupants. It allowed them to imagine repair or reform.

And then there was the other thing. The thing beneath the grievances. The thing that did not want to be named because once named it would demand consequences.

Monarchy.

What cannot be named cannot be resisted. What is never resisted learns to rule. We do not follow kings because they are strong; kings are strong because we follow.

Nor was it about this king. Nor a bad king. Nor a misunderstood king. The idea itself. A crown is a costume; a throne a story; a subject a role.

All of it ill-gotten: Preverse. Accursed. Unjust.

The belief that a family might inherit rights to rule by accident of birth. This notion, is always and forever Evil.

We make a crown to justify obedience, and then obedience justifies the crown.

I remember writing the word and stopping. Listening for footsteps. I knew this sentence, once printed, held wages of death.

Tis Truth: We do not obey because we are ruled; we are ruled because we obey.

I thought of England. Of the Excise Office. Of the endless explanations for why injustice was regrettable but necessary. Of how often necessity turns to the most convenient lie power ever told. I thought how easily men confuse tradition with wisdom and age with legitimacy. I thought of how much cruelty has been permitted because it wears a crown.

The sentence did not soften when I read it back.

It frightened me. Not because it was extreme, but because it was plain.

Once you say the thing clearly, you belong to it. There is no return to ambiguity. No denial. You cannot pretend you meant something else. I understood, with a grim calm, that I had written words for which there would be no pardon.

I set my pen down. The room felt intimate, as if it had been listening. I paced, three steps to the wall, three steps back. I imagined reactions. The outrage. The accusation of sedition. Ingratitude. Madness. I imagined silence, which would have been worse.

And then I imagined something more. A reader laying the pamphlet aside and feeling fortitude. The courage to know Loyalty had become habit and what they had called prudence, fear. The understanding that liberty does not coexist with obedience. Only one survives.

Benjamin Rush did not read quickly.

That is what I remember most. Not his words, but the way he held pages, the stillness as his eyes moved. A physician’s gaze. The kind that diagnosises.

We were indoors, out of wind. The room smelled faintly of medicines and old books. Orderly. I watched his hands more than his expression. Hands tell you whether a man is uneasy. His were not.

I had brought him sections, not the whole. I was not coy. I was cautious. It is easier to reject a fragment than a finished thing. He read without interruption. No nodding. No frowning. Silence stretched. I felt again that tightening revisit as when I first named the enemy.

When Dr. Rush finished, he laid the pages down, aligning edges, as if the argument required physical order before address.

“This will not be forgiven,” he said.

It was not a warning. It was a fact. Rush did not believe in softening Truth for comfort.

He asked questions. Not about logic. About its effect. Who would read it. How quickly it might spread. Whether I understood what it would mean to publish it now, not later, not softened by events, but now, when many still spoke of the king with a kind of embarrassed affection.

Rush said the title would not do. That it sounded defensive. That it suggested a rebuttal rather than declaration. He said the strength of the argument lay in its inevitability. He said it needed a name that made people feel foolish for having waited so long.

“Common Sense,” he said, almost offhandedly. His words landed.

They did not flatter a reader. They challenged. To disagree would be to admit deficiency. I knew at once Rush was right. I knew, too, that it would make enemies. Men do not forgive being told that they lack sense.

He spoke of anonymity. Not as an option. As a requirement. He said that attaching my name would end the pamphlet’s life before it had begun. That the argument needed to move faster than the authorities could attack an author.

I left with a curious calm. Not confidence. Rush had not tried to temper. He aimed to protect velocity.

I imagine the first reader unfolding it, seeing no name, feeling faint irritation that comes with an absence. Who dares speak so plainly? Who assumes such authority? The irritation will give way, I hope.

That is the gamble. That by removing myself, I enlarge ideas.

As I walk, I become aware of eyes. Or the idea of them. A man pauses too long. Another turns. It may be nothing. It may be the ordinary suspicion of a city at war with itself. Still, anonymity cuts both ways. To be unnamed is also to be unprotected. If the words provoke anger, there will be no intermediary to absorb it. It will look for a body eventually.

It is difficult to say when suspicion becomes atmosphere.

I tell myself this is imagination. That a man who has just released an argument like this is bound to feel exposed. That I am mistaking consequence for surveillance. Still, feelings persist.

Philadelphia has always been porous. Ideas move through it the way goods do. So do informers. Loyalists sit quietly in taverns. Officers dine politely with men who pretend neutrality. Information leaks not through speeches but through casual remarks.

It is tempting to dramatize. To imagine agents dispatched. Orders given. Lists drawn. Power rarely moves with drama. It moves with paperwork. Power prefers paper: Petitions, permits, then punishments.

Tyrannical power prefers quiet rooms: Quiet people and questions asked softly.

What unsettles me is not the idea of arrest. It is the idea of being explained. Of having argument reduced to motive. Of being recast as foreign. Resentful. Unstable. England taught me how efficiently this can be done.

I think again of Rush’s warning. This will not be forgiven. Forgiveness implies a face. Punishment does not require one.

The street opens up ahead. Light shifts. The river glints between buildings. The city continues as if nothing has happened, which is always how it looks at the start of something.

If danger is forming, it will take shape elsewhere, around the words. That is where I want it. Let the argument draw fire.

Scripture is the one text everyone shares. You can disagree about its interpretation, but you cannot deny its authority. It tells them when a statement is meant to matter. I borrowed that authority deliberately, the way one borrows a tool that is proven.

Some will say this is manipulation. They will not be wrong. All persuasion is manipulation of attention. The only question is toward what end.

I was not invoking God to sanctify rebellion. I invoked familiarity to strip away excuse.

When I wrote society is a blessing and government a necessary evil, I did not pause to justify. I let it stand. Necessary evil. Fact.

I was careful not to preach. Preaching asks for submission. I sought consent. The Bible’s power lies not in demands but in assertions. It states. It declares. It leaves you alone with the consequences of consent or refusal.

I had known, that words can provoke anger. I had imagined rebuttals and denunciations. What I had not fully considered was the speed with which the argument could move.

This is the danger of clarity. It has velocity.

If I have misjudged the moment, there will be consequences. But I have lived long enough to know misjudging delay carries consequences too, though they arrive dressed as patience and restraint. Men call it prudence. History calls it failure.

I do not imagine revolution. That word belongs to men who prefer geometry to weather. I imagine argument. Spread. Resistance. I imagine being denounced by people who have not read. I imagine others reading and saying nothing at all, which is always more damning.

What I hope for is quieter. I hope for a shift in vocabulary. For the word “king” to sound faintly ridiculous in a continent full of land. For “inheritance” to lose its moral authority when applied to power. For men to begin asking not how to be governed better, but whether they should be governed in that way.

I stop and listen. Somewhere a voice rises and falls, reading. I cannot hear the words. I do not need to. The cadence is enough.

I turn away and keep walking. Unnamed. Unaccompanied. The argument has already moved on, carrying itself where I cannot follow.

Whatever comes of it will come.

NOTE:

Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense” was published by Robert Bell in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on January 10, 1776. The first 1,000 copies sold out within a week. By July 4th of that year, historians estimate 150,000 copies in a nation of 2.5 million (about 60% literate) circulated. The pamphlet is roughly 20,000 words and took 60 days to pen. Paine said plainly what had not been said before but was brewing: It made no sense to be ruled by someone who inherited power. As written words go, Common Sense was the literary spark that ignited our American Revolution.